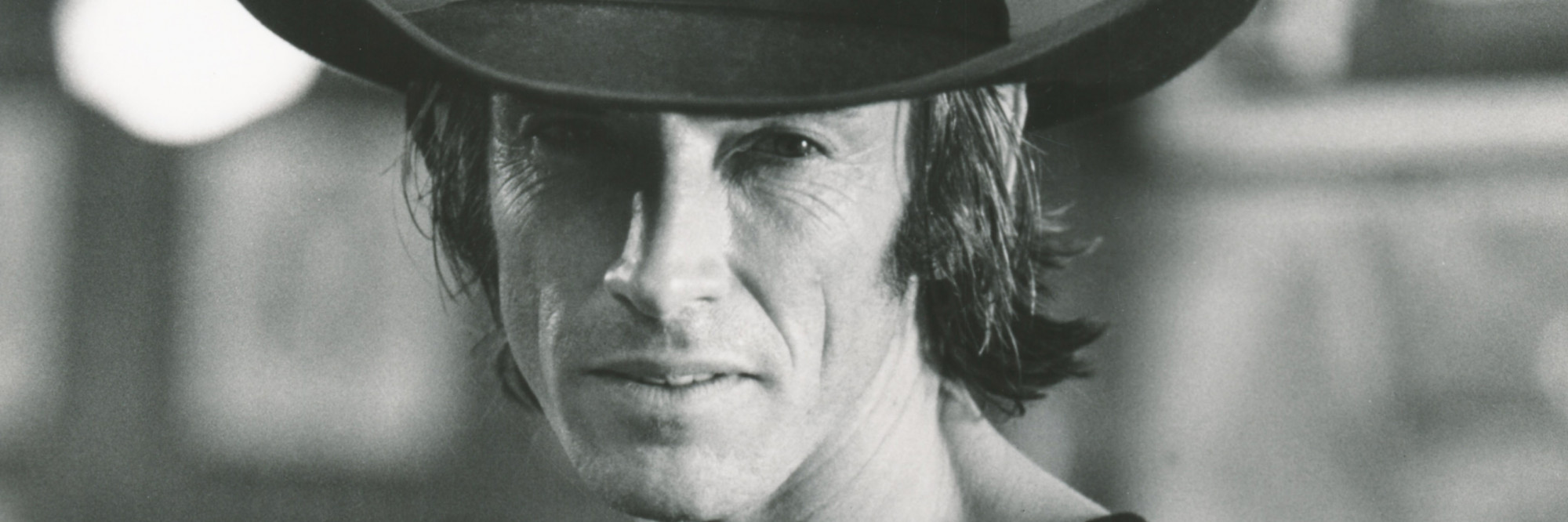

Tribute Scott Glenn

When the part plays you

As a former Marine and surgeon, Eugene is a man of discipline and unbreakable habits. Each of his days begins with a rigorous fitness routine, which includes numerous push-ups, as practiced by soldiers, as well as exercises with a combat knife. It's fascinating to observe the endurance and naturalness with which this man, who is well over 80, trains.

It is these repeatedly repeated training scenes in Hank Bedford's »Eugene the Marine« that seem to define the man played by Scott Glenn. During these exercises, Eugene radiates a calm and serenity that he otherwise finds increasingly difficult to maintain. For this time, he is completely at peace with himself.

Interviews reveal that Scott Glenn, born in Pittsburgh in 1939, follows a very similar fitness routine every day. In this respect, these scenes in Bedford's slightly surreal thriller have an almost documentary quality. The line between Glenn and his role seems to blur. Eugene and Scott Glenn's stoic workout regimen also reveals something like the essence of Glenn's on-screen persona. While watching him exercise, one's thoughts inevitably wander back to films like James Bridges' »Urban Cowboy« (1980) and Philip Kaufman's »The Right Stuff« (1983), John Frankenheimer's »The Challenge« (1982) and Jonathan Demme's »Silence of the Lambs« (1991), John McTiernan's »The Hunt for Red October« (1990), and Ken Loach's »Carla's Song« (1996). All of Scott Glenn's performances, both large and small, have one thing in common: His characters initially captivate the viewer with their physical presence. In »Urban Cowboy«, this affectionate yet unsparing homage to the world of honky-tonks, his physical acting exerts an almost magical attraction. It's no wonder that Debra Winger's Sissy, despite her love for John Travolta's boyish Bud, feels drawn to his portrayal of Wes Hightower. Glenn radiates such energy and self-confidence in the role of the modern outlaw that he barely needs words. The dark, destructive sides of this archetypal figure of American cinema, who comes from the

Western tradition, are also ever-present in his supple movements, his piercing gaze, and his mocking smile.

His dazzling and seductive embodiment of all the darkest aspects of the American myth in »Urban Cowboy« finally opened all doors in Hollywood for Scott Glenn, who was in the Marines in the 1960s and initially aspired to a career as a journalist and author. He also owes his first leading role in John Frankenheimer's »The Challenge« to it. The hapless boxer Rick, who, in classic noir style, is hired for a job that soon becomes too much for him, is, on the one hand, a variation on Wes Hightower and, on the other, the antithesis of that character.

Rick, too, dominates every situation through his physical charisma alone. But unlike Hightower, he is initially barely able to capitalize on this effect. In»The Challenge« Glenn plays with another archetypal American myth. Rick is the American detached from all ties to tradition and history, living only in the moment and lacking stability. A stability, he can only find it in the world of the descendants of the Japanese samurai – a world that stands for structure and discipline. It is this discipline that also Eugene represents at the beginning of »Eugene the Marine«, that characterizes Glenn's acting in each of his films.

In a way, Glenn, like Clint Eastwood, should have become one of the great stars of modern genre cinema. His physical presence and stoic manner predestined him for the role. However, Hollywood took a different direction in the 80s and 90s than what a film like »The Challenge« offered. B-movies starring Chuck Norris and Steven Seagal took its place. So, Glenn was mostly offered character and supporting roles in major studio productions, and most recently, appearances in series like »The Leftovers« and »Castle Rock« »Bad Monkey« and »The White Lotus«, to which he could lend his ever vivid charisma and class.

URBAN COWBOY

JAMES BRIDGES | USA 80

Bud Davis, played by John Travolta, leaves his parents’ home and the small town where he grew up. He wants to earn money in the big city to one day buy himself a farm. When he meets Sissy (Debra Winger) in a nightclub, he falls head over heels in love. The two quickly marry – but their relationship soon unravels under Bud’s jealousy of Wes Hightower, an ex-con and bull rider portrayed by Scott Glenn.

A film like a time capsule. As a precise portrait of the world of Texas factory and oil workers and their families, and of an era – the late 1970s – »Urban Cowboy« (1980) exerts a remarkable pull. James Bridges’ melodrama, almost archetypal for its time, draws the viewer deep into the initially unfamiliar world of »Gilley’s,« the massive club run by country musician Mickey Gilley. At the same time, the film surprises and unsettles with the matter-of-factness with which Bridges depicts domestic violence. The blows Sissy suffers at the hands of Bud and Wes are presented as something ordinary – which makes them all the more painful. In this lies a warning that lends »Urban Cowboy« a deeply disquieting relevance today

THE CHALLENGE

JOHN FRANKENHEIMER | USA/JAP 82

When John Frankenheimer’s modern samurai film »The Challenge« was released in 1982, it was often dismissed as little more than a cynical orgy of violence. Even today, it remains far less known than other works by this auteur, who had a rare gift for breaking through the limits and conventions of genre cinema.

Here, too, he does so in the story of a failed American boxer who becomes entangled in a long-standing feud between two brothers in Japan. The struggle over two ancient samurai swords, kept in the family for centuries, is not only a battle between Yoshida (played by Toshirô Mifune) and his younger brother Hideo (Atsuo Nakamura). Scott Glenn’s Rick, searching for stability and redemption, also finds himself caught between the forces of tradition and modernity, between the values of the samurai and those of capitalism. It is precisely this fracture that Frankenheimer weaves into every moment of the film. It lends the fight sequences – choreographed with striking precision by Steven Seagal – and the brutal eruptions of violence a unique force and depth. In them, a society in the throes of a violent transformation is laid bare.

THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS

JONATHAN DEMME | USA 91

»The Silence of the Lambs« (1991), Jonathan Demme’s adaptation of Thomas Harris’ bestseller, is without question one of the milestones of modern Hollywood cinema. The story of FBI agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), who falls under the spell of serial killer Dr. Hannibal Lecter, firmly anchored the figure of the serial killer in popular culture. As a result, Demme’s film often feels familiar.

And yet, it is worth setting aside everything it spawned and rediscovering it anew: as a masterfully crafted thriller that distinguishes itself from its

successors through its subtle Gothic atmosphere and a range of settings that evoke the early 20th century more than the 1990s. One is struck, too, by how sparingly and effectively Demme deploys violence – suggesting more than he ever shows. The sensationalism of later serial-killer films is nowhere to be found here.

Instead, Demme focuses entirely on the performances of Jodie Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Ted Levine, and Scott Glenn. As Clarice’s mentor, Glenn delivers a quiet, understated portrayal of a man whose work as a profiler gradually permeates every aspect of his life.

CARLA'S SONG

KEN LOACH | USA 96

Scott Glenn appears late in the film, and only in a handful of scenes. Yet he and his character – Bradley, a former CIA agent who has switched sides and now works for a human rights organization during the Contra guerrilla war against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government – stand at the heart of Ken Loach’s »Carla’s Song« (1996).

While driving his bus through Glasgow, George (Robert Carlyle) encounters Carla (Olyanka Cabezas), a deeply traumatized young woman, for the first time. When he later sees her again, dancing in a pedestrian zone to collect money, he is so captivated by her that he upends his entire life. He manages to build a relationship with the woman from Nicaragua and eventually persuades her to return to her homeland with him, so that she can confront her demons. Amidst the war, they encounter Bradley, who finally opens George’s eyes to the political reality of Central America. Thus Ken Loach’s melancholic portrait of love in times of war transforms into a searing indictment of the United States’ neo-colonial foreign policy.