Retrospective James William Guercio

Cinema of Loneliness

The idea that humankind could subdue the earth was always sheer hubris – just as the notion that the American West and Southwest could ever truly be conquered, let alone civilized. In the face of nature, humanity amounts to little more than a fleeting episode in the planet’s history. Though it drives the earth to its limits, and beyond, it remains a tragicomic interlude. Director James William Guercio and cinematographer Conrad Hall found an unforgettable image for this truth.

At the end of »Electra Glide in Blue« (1973), motorcycle cop John Wintergreen, played by Robert Blake, sits slumped on the center line of a highway, fatally wounded by shotgun blasts. The camera pulls back – further and further – and as the figure of the man dwindles in the frame, the stark yet majestic landscape of Monument Valley, with its iconic rock formations, comes to dominate the composition. Wintergreen, the victim of a senseless and yet almost inevitable murder, dwindles into a black speck on the asphalt before disappearing entirely. Overhead, a solitary eagle circles the highway. This final camera movement ranks among the most iconic images of American cinema – comparable only to the closing shot of John Ford’s »The Searchers« (1956) or the long final minutes of Martin Scorsese’s »Taxi Driver« (1976).

Yet unlike those films and their legendary auteurs, »Electra Glide in Blue« and James William Guercio are known only to aficionados of late-1960s and 1970s cinema. The reasons for this obscurity could themselves be the stuff of legend. Legends like these: the bloodbath at the end of »Taxi Driver« may stand as one of the great extreme, transgressive moments of New Hollywood. But its radicalism lies in shock and excess – tailor-made to provoke attention and controversy. The radicalism of »Electra Glide in Blue« is of an entirely different order: quieter, but ultimately more unsettling. It disoriented and disturbed audiences and critics alike in 1973. Some even claimed to detect in the story of a failing cop the outlines of a proto-fascist law-and order mentality.

Indeed, figures such as Wintergreen’s partner Zipper (Billy Green Bush) or homicide detective Harve Poole (Mitchel Ryan) harass and brutalize hippies at every opportunity, and their attitudes are undeniably fascistic. But none of them are remotely sympathetic, let alone points of identification. In them, the neurotic and paranoid side of a society is revealed – a society clinging to outdated notions of order in a time of crisis and upheaval. Yet the hippies whom Wintergreen encounters are hardly more inviting as figures of identification. It is clear that the outsider Wintergreen – who dreams of a homicide post and has far deeper insight into peo ple and their motives than Poole – feels closer to them than to his colleagues. But they, too, seem ultimately adrift, their former ideals abandoned, trapped in a present without a future.

And so only Wintergreen remains, a man between worlds, forever moving along the median strip, belonging nowhere. Robert Blake’s John Wintergreen – small, at times almost ridiculous, and yet heroic – is, even more than Travis Bickle in »Taxi Driver«, »God’s lonely man.« A lonelier figure is hard to imagine. In this, Guercio’s feature debut crystallizes a tendency that defined much of New Hollywood cinema. »A cinema of loneliness« – as American film scholar Robert P. Kolker famously called it – and yet Kolker passed over the very film that gave this »cinema of loneliness« one of its greatest achievements.

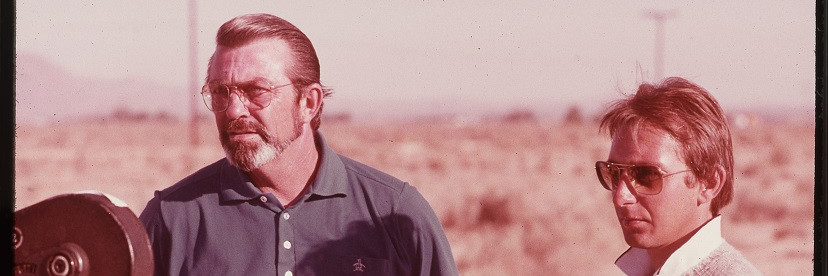

Before directing »Electra Glide in Blue,« Guercio had already made music history as producer for bands like »Chicago« and »Blood, Sweat & Tears.« Later, with Caribou Ranch, one of the most sought-after recording studios of its time, and with Caribou Records, he continued to shape pop music. In a way, it was precisely this sensitivity to pop, this instinct for the signs of the times, that made his sole directorial effort one of the

most exhilarating films of the early 1970s. Few filmmakers captured the mood of America in those years as Guercio did.

John Wintergreen’s loneliness is not only existential, not merely existentialist – it is also the expression of a profoundly divided nation that has lost its center. Wintergreen, who only wants to do the right thing and still believes in the American Dream, is inevitably pulled between all sides, finally to become the victim of division and radicalization. That is what makes James William Guercio, this great chronicler of his time, a

visionary – and his film a portrait of our own present as well.

Electra Glide in Blue

At first glance, James William Guercio’s sole directorial effort could be mistaken for a conventional police drama. After all, its story centers on motorcycle cop John Wintergreen, played with remarkable intensity by Robert Blake. Wintergreen is desperate to escape the monotony of traffic duty and the endless chase after speeders; he longs for a position in the homicide division. When he discovers the body of a man who has died under mysterious circumstances, his dream suddenly seems within reach. Yet just as Blake, with his portrayal of a profoundly lonely outsider, undermines the Hollywood image of the tough cop, Guercio defies nearly every convention of the genre. The case itself becomes less an investigation than a crystallization point: it reveals the inner lives of those connected to it and, at the same time, serves as a mirror of American society. Rather than a straightforward, action-driven cop thriller – though flashes of that surface in certain sequences – Guercio has created an unforgettable mood piece. It captures with startling immediacy what it must have felt like to live in the United States in the early 1970s – and what, perhaps, it feels like once again today.